In 1785, the English inventor Edmund Cartwright unveiled a working prototype of an automated loom. For the first time in history, a piece of fabric was woven without the use of human hands. It was powered by a water wheel and made very low-quality cloth. This initial loom turned out to be a complete failure economically. Quality be damned, the seeds of innovation were sown, and the industrialists of England were off to the races, re-inventing and revising machine powered looms. Soon enough, it became impossible for fabric producers anywhere in the world working on hand looms to compete with the prices and volumes that were rolling out of England’s ever-expanding factories. The world had changed forever.

By the early 19th century there was a growing number of textile workers within England who started questioning this change. These weaving machines were taking away their jobs. They named themselves the Luddites, after Ned Ludd, a legendary (and probably fictional) worker rumored to have destroyed weaving machinery in a fit of rage. He was a symbol of the workers revolt against automation. The Luddites believed that the new machines were not only taking away their livelihoods, but also reducing the quality of the textiles they produced. They staged protests and sometimes resorted to violence, attacking factories, and destroying the new machinery. The government eventually cracked down on the Luddites, and the movement largely died out by the mid-19th century.

AI Has Been Opened

Last month the company OpenAI launched their new chat bot chatGPT to the public. By signing up for an account, anyone can ask questions to the AI software and have it complete simple tasks. Like most new things on the internet, I first used this software to make jokes with friends. I pushed to find the limitations of the chat bot by slowly increasing the absurdity of my prompts.

It could write fictional stories about other people in the room within a desired genre, suggest the appropriate emojis to use given specific contexts, and even give guidance on how big your ‘doughnut wall’ should be at your wedding.

The next day I asked the chat bot to help write captions for a few Instagram posts in the style of a Zen poem. The results were surprisingly good! They were also generated in less than 3 seconds.

“In the stillness of the loom, a thread of wool becomes a work of art. Hand-woven with love, our rugs bring warmth and harmony to any space”

“The gentle rhythm of the shuttle, the delicate interplay of colors, the softness of the wool underfoot. Our rugs are a celebration of the beauty of simplicity and the art of mindfulness”

“From the fields of India, to the hands of skilled craftsmen, to your home. Our wool rugs are a journey of tradition, passion, and connection.”

I took a screen shot of the chat and posted it to Instagram to gauge people’s reactions. Many people showed concerns of the software leading to job loss, and a general hollowing of the work being completed. It’s important to note that ChatGPT gets many things wrong. Like the first loom by Cartwright, this is not the version that will be taking your desk job. It does however seem to be the first prototype shared with the public that shows promise new tech will be automating a wide range of white-collar work.

The Food Is Terrible, And In Such Small Portions

Let’s imagine a large chunk of office work is automated away. Legal contracts can be created and tailored by someone with no training, customer service becomes immediate and incredibly flexible, and software code can write itself. Which of these jobs would you do if you weren’t getting paid to do it?

It's important to note, all tasks that AI can complete will still be available to us, just like anyone can hand weave fabrics. AI cannot rob us of producing paintings, writing poetry, or enjoying the act of baking. However, I don’t pretend that the weavers I work with in India are producing textiles for enjoyment. They are skilled trades people who weave to make an income. There are a few reasons that allow my company to buy and sell hand woven rugs in an age of automated looms.

Firstly, the industrial revolution is ongoing. India continues to keep many traditional production methods alive through a massive rural population that does not yet have access to the goods, services, and basic infrastructure we have in the west. We have also reduced the friction between borders and allow goods and services to flow between them, allowing people in India to have more access to our markets.

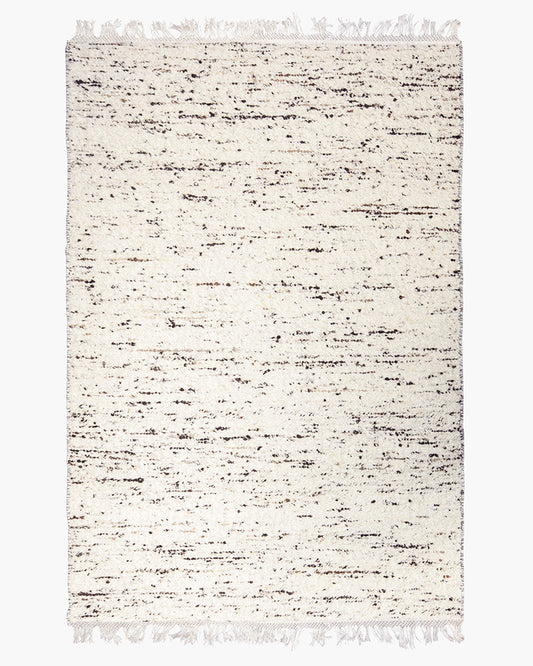

Secondly, automated looms over the last 200 years got much better at making uniform quality, overtaking hand loomed fabrics within the context of modern design principles. Machine made fabrics are stronger, more intricate, and perfectly uniform, all while costing less. This has led to a shift in aesthetic values, with most fabrics being produced by machine, and a (relatively) small market who see the beauty in the flaws created by the human hand.

Automated looms cannot be perfectly imperfect. The slight corrections and judgements made by the weavers at every yarn pass produce a quality in hand made rugs that is difficult to put into words. Automated looms also don’t like yarns that are perfectly imperfect, meaning the machine needs highly processed yarns, usually with a percentage of synthetic fibre or even 100% synthetic fibre. Natural fibres, similar to humans, also have flaws. You can’t make a sheep grow uniform wool. An imperfect wool yarn breaks a machine loom, but a weaver just adapts. The hand-feel of loosely spun 100% wool yarn is hard to beat, and hard for a machine to replicate.

The 15 Hour Work Week

In contrast to the slow century creep of industrialization, the risk from AI comes at the possible speed and scope of what can be automated. It’s possible that within a decade or so, AI could not just automate many lower income jobs, but also big chunks of middle-to-high income professions, all while pooling money in the hands of the few owners of such tech. Some nations will be better positioned than others to respond.

The automation of the loom and the subsequent rise of the luddites was that of financial strife with laborers and the owners of the technology, acting as an early movement towards workers rights, unionization, and new political ideologies. It’s worth noting Karl Marx wrote the communist manifesto in response to worker treatment within English textile factories.

In 1930, riding on incredible growth of labor-saving technologies the economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that his grandchildren would work just 15 hours a week. Of course, this turned out not to be the case. Humans are very good at inventing new jobs. It is possible we are at the beginning of a new economic era, and that the future holds ever more human driven tasks we couldn’t have thought of today. It would have been hard for a grandfather 80 years ago to imagine their grandchild having a thriving career as an online yoga instructor.

Instead of our best and brightest pouring into high-paying app start-ups, investment companies, and law firms (professions in which AI will likely be early to tackle), they focus on re-populating the collapsing ecosystems of our oceans, work with people living on the street to help stabilize their lives, or experiment with biodiverse agricultural practices. Or maybe they just spend their days writing poems for the people in their lives.

Yes, AI may be different than all other creative destruction that has come before it. The space between technology and biology seems to be blurring and we may finally be reaching the end of work as we know it. This could mean utopia, or dystopia. I have a feeling the future lands somewhere in-between.

1 comment

thank you for this thoughtful and insightful post – there are indeed interesting times ahead