Photo: Mandy Barker- EVERY snowflake is different

In Canada, we toss away 3 million tonnes of plastic each year. Most of this is plastic packaging. Only 9% of plastic is recycled. The rest ends up slowly seeping into our soil, lakes, and oceans, whether that is within Canada, or in another country which we pay to receive this garbage. In 2021, 14% of Toronto’s plastic was sent overseas. Not only are we not recycling this plastic, but Canada incinerates 4% of plastics that are consumed. We are burning half of the equivalent amount of plastic we recycle.

So why are we doing this? The simple answer is there is a lot of money to be saved in using plastic packaging. Say you are a multi-national corporation selling various types of sugar water. You have a product with incredible margins, and a plastic packaging solution that costs roughly 2.6 cents per bottle, is extremely durable, and extremely light weight. Of course, there is a problem. These bottles take 450 years to decompose, and it can only be used one time. The marketing department has been working on a solution, tell the end consumer to recycle.

The lie here can be found directly in the marketing copy, RE-cycle, suggesting a cyclical system in which the end of one products life feeds back into the start of another. But this sugar water company uses 100% virgin plastic. All plastic purchased at a grocery store, and all plastic used for takeout is new plastic. They must use virgin plastic which are the only food safe plastic, and are only food safe for a single use. After that the plastic starts leeching and if re-used will slowly poison the food it holds. Other than a few fringe material development breakthroughs, almost no food safe recycled plastic packaging materials are currently on store shelves.

Even if we could increase our plastic ‘recycling’ programs from 9% to 100% of waste, there currently is no cycle. That is the heart of the problem, we will always have plastic waste if we are producing primarily virgin plastics.

Yes, there could be a future where we start taking advantage of more recent developments in plastic recycling. There are now recycled PET plastics being approved for food use (although with limited interest from the food container industry). But the main conversation should not be around improving our clearly broken recycling program. We have been ‘working’ on this for 50+ years with 9% to show for it. I also have a sneaking suspicion that these plastic recycling ‘breakthroughs’ will always conveniently be around the corner, and that is exactly how the current plastics industry likes it.

This is why I believe a solution to the problem lies in accountability and governance. Let’s start with relationships. The existence of almost all plastics starts between a supplier and a consumer. Both are responsible, and both need to be held accountable. With our current system we place all the responsibility on the consumer to properly use and dispose of the plastics. The supplier also needs to be involved in collecting, reusing, or disposing. We already have this system for glass bottles. If sugar water companies had to accept their packaging back, at the very least they would develop a system where they would find secondary use (and not just for 9% of the bottles).

Holding plastic suppliers accountable for their products hinges on the second part of this proposed solution, government intervention. There is a small movement growing now in the Canadian government under the ‘zero plastic waist agenda’ but with not too much to show for itself yet. As a first step at the beginning of this year the government banned a handful of single use plastics such as stir sticks, and six-pack rings. The ban took an additional two years to implement due to massive corporate pushback via feasibility studies and good old fashion lobbying.

These gains show the massive undertaking for the smallest tweaks to our current way of consumption. These changes need to be discussed outside of the framework of the individual. How are we meant to make a meaningful difference when the general public doesn’t even know what these materials are?

We call them ‘plastics’, but plastic is the state of the material, not the material itself. These materials are called polymers, and according to the recycling symbol system found at the bottom of your plastic bottles (the number in that three-arrow triangle symbol), there are 7 types, with #1 and #2 being the most widely accepted types of plastic that are recycled. #3-#7 tend not to be recyclable in most systems. Here is the kicker, #7 represents ‘other’ in the system. Number 7 is every other type of polymer that exists. The more I investigate plastics, the more I realize we, the public, know nothing about these materials, yet every one of us interacts and disposes of them every single day (A side note here of something I found while researching this newsletter: black plastic is not recyclable. It does not matter what type of plastic it is; it cannot be processed at recycling facilities. The reason we still produce black plastic is beyond me. This seems like the simplest change imaginable as it is just aesthetic.).

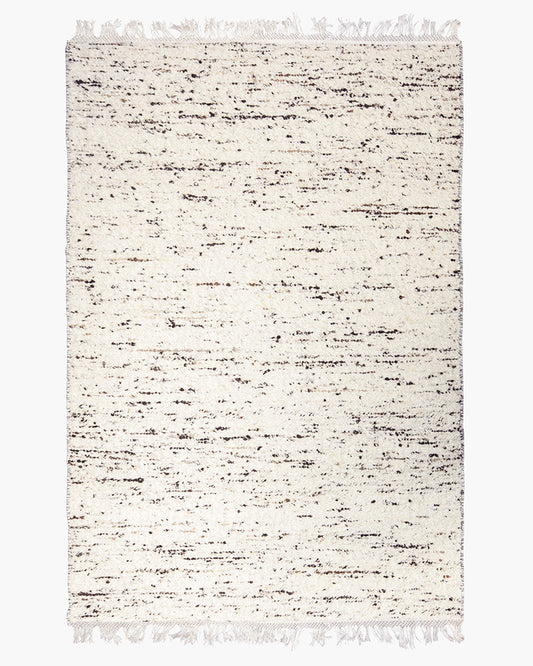

That brings me to the plastic use of my own company. All rugs produced by Mark Krebs are double packaged, first in a clear watertight polypropylene bag to keep moisture content at acceptable levels as to not cause mold or decay, then in a durable white woven polypropylene outer bag to insure no damage in transit. Both these materials are technically recyclable, but will not be, even if the end consumer sorts them correctly. I do not currently have another option. I am limited by what my rug weavers have available in their local markets. Also, what is most important environmentally speaking is that my rugs arrive undamaged, which plastic does and incredible job at. Think about the wasted material, transportation and labour involved in producing my rugs if even a small percentage of rugs were damaged in shipping.

I’ve been considering a way to somehow try and collect my packaging so I could bring it directly to a recycling plant pre-sorted by colour and in bails (insuring 100% will be used, albeit downcycled), but the logistics of returning plastic packaging has its own ecological footprint, not to mention price tag and labor for the end consumer.

The next logical step would be fully recyclable rug bags, which can be collected and sent back to the weavers. This solution faces the same issues as above, but with the additional complexities of getting them back to rural areas of India. This would be my ideal solution, and as I scale I could start trying testing with my suppliers in India.

I do not believe compostable packaging is feasible in the form of composting plastics. Not only because it is currently incredibly difficult (if not impossible) to supply to my weavers, but also because compostable plastic tends to be made from corn, which is food. Call me coo-coo, but we should eat food.

Ultimately, the packaging of high value items is at the bottom of the list of changes needed in the plastics industry as the importance of that packaging to deliver the item without damage is most critical. If a high value item is damaged, then a massive amount of resources have gone to waste. But we are currently in a position where we need to re-think an entire industry, so I will need to eventually find a long-term solution to eliminate plastic waste from my rugs.

We do need an immediate solution to plastic packaging for food products, which make up a huge chunk of plastic waste. The first step is everyone admitting that plastic recycling is not a thing and will never be a thing. We need to start thinking about the problem of one that both consumer and producer need to take responsibility for, and for governments to create policy that holds everyone accountable. If we keep allowing industry to leave consumers quite literally ‘holding the bag’ we will continue to destroy aquatic ecosystems and poison the drinking water of the poorest people on this planet.

Next time you are unsure if plastic you are tossing away is recyclable or not, just throw it in the trash. At the very least you are consciously taking ownership of the fact it is going into a land fill. If we continue to ignore that 91% of our plastic is not being recycled, we will never make any meaningful change.

6 comments

The plastic waste problem in Canada is staggering, with millions of tonnes discarded each year, and only a small fraction getting recycled. The harsh reality is that much of this plastic ends up polluting our environment or being shipped overseas, where it’s out of sight but still causing harm. It’s frustrating to see that the driving force behind all this waste is the cost-saving benefits for large corporations. Plastic packaging is cheap, durable, and convenient, so companies continue to use it despite the environmental toll. Meanwhile, the burden of recycling is unfairly placed on consumers, while the real issue—overproduction and reliance on single-use plastics—goes largely unchecked. It’s clear that we need a shift in how we approach packaging, prioritizing sustainability over short-term savings. For more insights into tackling waste, check out https://diaperrecycling.technology.

In Canada, we discard a staggering 3 million tonnes of plastic each year, primarily in the form of packaging. Sadly, only 9% of this plastic is recycled, with the rest gradually contaminating our soil, lakes, and oceans—whether within Canada or in countries we pay to handle our waste. In 2021, 14% of Toronto’s plastic was sent overseas. Additionally, Canada incinerates 4% of its plastic, burning half of what we manage to recycle. The root of the problem lies in the cost-effectiveness of plastic packaging. For instance, a multinational corporation selling sugary beverages benefits from plastic bottles that cost just 2.6 cents each to produce, are durable, and lightweight. However, these bottles take 450 years to decompose and are designed for single use. The marketing department’s solution? Encourage consumers to recycle, shifting responsibility to the end user while systemic issues with plastic production and disposal persist. For innovative approaches to recycling and sustainability, visit https://diaperrecycling.technology/innovations/.

Thank you for thinking and speaking and educating on this very important, overwhelming issue.

Thank you for your brilliant letter. It confirms what l have been wondering about for years. Back in the 80’s the hospital switched from stainless steel and cloth OR or dressing trays to plastic recycled materials including plastic tweezers. I never understood why. You have raised excellent points here. I appreciate your insights and your conscientious approach to your business. Thank you for that.

I believe only government intervention forced on them by voters will make any impact on the problem. Water bottles would be a good starting point. Thanks for sharing and hopefully voicing our opinion to those who can change the system will make a difference.